Sometimes, suspense is low in a story because . . . well, the hero(ine)’s never really in danger. Obviously, not all stories require the hero to risk his life or the heroine to save the whole! world!, but, as Hitchcock said, “The stronger the evil, the stronger the film” (Traffaut 316). Or, you know, book.

This can be especially apparent in the middle of the book. James Scott Bell says “If your  readers aren’t worried about your Lead because the opponent or opposing circumstances are soft, the middle will seem like a long slog indeed” (229).

readers aren’t worried about your Lead because the opponent or opposing circumstances are soft, the middle will seem like a long slog indeed” (229).

Naturally, we have to start with a strong antagonist, well-matched to our Lead. That doesn’t mean, of course, that the readers have to know who he is—most mysteries revolve around that revelation (whereas most suspense novels revolve around already knowing who he is—greater information, greater suspense. Thanks again, Hitchcock.). We just have to know he’s bad, he’s dangerous, and he’s after our Lead.

We’ve already talked about The Complication of Act II from Fiction First Aid by Raymond Obstfeld, because strong plotting methods include specific events to help us show our antagonists’ strength.

In Larry Brooks’s Story Structure, for example, Act II contains two “pinch points” that are designed to raise the stakes by showing us just how bad the villain is. Even the Mid-Point is designed to help with this, showing the hero more to the story, changing the way he views the world.

James Scott Bell’s Revision And Self-Editing gives more advice on better arming the antagonist, drawing on the “three aspects of death“:

- Does the opposition have the power to kill your Lead, like a mafia don, for instance?

- Does the opposition have the power to crush your Lead’s professional pursuits, like a crooked judge in a criminal trial?

- Does the opposition have the power to crush your Lead’s spirit? Think of the awful mother played by Gladys Cooper in the 1942 film Now, Voyager. She has that power over her daughter, played by Bette Davis. (229)

I especially like Bell’s advice because it applies to more than just life-and-death suspense. Make sure as you arm your opposition that they don’t become “a caricature,” Bell warns—show their shades of gray. And if you end up making your opposition stronger than your Lead, strengthen your Lead to match the villain next.

What do you think? How else can we arm the antagonist?

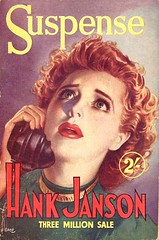

Photo by Jim Barker

I like having the Antagonist crossing the moral lines the Protagonist won’t cross…especially the ones that piss of the protagonist the most.