In my opinion, the best way to truly make setting a character is to have some conflict for the characters arising from the setting. It may sound specialized, but the setting probably provides opposition to characters’ goals in some form in almost any work of fiction.

In its most obvious form, setting can provide the main conflict of the story, as in disaster fiction. This use of setting always makes me think of movies like Twister, The Day After Tomorrow, or 2012.

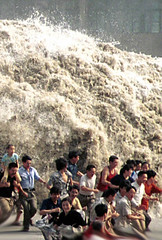

The disaster genre uses setting very effectively on a macro level. A natural disaster—be it hurricane, tornado, earthquake, fire or flood—stands between our heroes and their goals. Often, the heroes’ goal is just staying alive, and, uh, dying really puts a damper on that.

The disaster genre uses setting very effectively on a macro level. A natural disaster—be it hurricane, tornado, earthquake, fire or flood—stands between our heroes and their goals. Often, the heroes’ goal is just staying alive, and, uh, dying really puts a damper on that.

Of course, natural disasters aren’t really characters. They may be the main antagonist in a story, but they’re still no villain. However, we have to establish that the disaster is truly a threat, if not evil (just like with human antagonists). And (also just like with human antagonists), the best way to do that is to show the antagonist in action: someone getting caught by the disaster, or its after-effects or foreshadowing.

Showing the natural disaster’s capabilities can be one form of the other end of the spectrum, a scene-level conflict arising from the setting. This type of setting-conflict is more common, and probably appears in almost any book. It can be something as simple as a traffic jam that makes our characters late for the big meeting.

Sometimes I find myself relying on setting for little conflict like this maybe a little too much, however. A traffic jam or two might not push our readers past their capacity for the suspension of disbelief, but if every time the star-crossed lovers are supposed to meet, the Interstate suddenly backs up, maybe the state DOT should get involved.

Even on a minor level, a simple setting change can increase the tension and conflict in a scene. One dramatic example of this comes from the movie Mr. & Mrs. Smith. If you haven’t seen it, it’s a movie about unwitting married assassins. When they’re assigned to kill one another, they discover their true identities and both question their flagging love and failing marriage.

In one particular scene, they “DTR” (define the relationship). John (Brad Pitt) begins “Let’s call this what it is,” meaning Let’s admit our marriage is a sham. It’s an emotional turning point for the characters—asking is this marriage worth fighting for anymore?

In the original scene, they had this conversation in a parking garage. I’ve seen this version—it falls flat. There’s no tension. It slows down the action side of the story.

Do you remember where they have this conversation in the final cut of the film? They’re hiding under a storm drain grate with the bad guys a few feet away. The characters are not only in a far more tense situation, they’re also forced to be physically close as they confront the reality of their marriage. The dialogue is identical to the originally shot scene, but in this new setting, the tension skyrockets.

What do you think? Do you try to use setting to create conflict? What’s your favorite setting-conflict (that you’ve seen or created)?

Photo by Adam Stanhope

Good thoughts, even difficult. You helped me see my antagonist might be a part of the setting, or maybe I have several antagonists. Thanks! I really enjoy your posts!