A version of this post originally ran on 12 July 2010.

Last summer, after I had baby #3, I went on a reading spree. I read a lot of great books, but after more than a month of devouring award-winning (and not so much) novels, I hit the wall. In less than a week, I started a number of books that just didn’t reel me in. They didn’t “seduce” me. Reading them was, frankly, a chore.

I did skip to the end of the novels, but largely so I’d never, ever be tempted to pick them up again. (If your novel makes sense without the middle 100 pages, something might be wrong…) Telling vs. showing was the main problem. I said it was like the author was standing in front of me, holding up a curtain as he dictated the action on the other side.

I did skip to the end of the novels, but largely so I’d never, ever be tempted to pick them up again. (If your novel makes sense without the middle 100 pages, something might be wrong…) Telling vs. showing was the main problem. I said it was like the author was standing in front of me, holding up a curtain as he dictated the action on the other side.

Although bad writing is always a turn off, it’s not always enough to make me give up on a book, or at least half of it. Some of the books I just couldn’t not put down lost me in character soup. Ten characters in the first five pages is way too many—especially when for some reason, we have to dip into each character’s POV for a paragraph or two, even if that character is 2000 miles away and not having a scene of her own! In another case, the story was told from one character’s POV, but by the end of the first chapter, we’d met so many people I couldn’t remember which character that was. And I kept forgetting in subsequent chapters.

I think both of these issues stem from the same problem: a failure to get the reader (me) involved in the characters. Something about the narration style (telling) was too distant or confusing for me to make an emotional connection and sympathize with characters. And I’m realizing that life’s too short for boring books (or boring novels, anyway), so I’m not willing to persevere through a hundred pages to see if I suddenly start liking a character.

No, I don’t believe characters have to be likeable to be sympathetic—but man, they have to inspire me to feel something!

What do you think? Why is emotion so important in writing? What keeps you from relating to a character?

Photo by Wade Kelly

But, just like in real life, emotion in fiction is tough. It requires just the right touch to know when and how to put it in, a fine balance to know when to leave it out, creativity to avoid clichés and reaching deep within ourselves for authenticity—possibly even exposing some of our hidden inner lives to the entire world.

But, just like in real life, emotion in fiction is tough. It requires just the right touch to know when and how to put it in, a fine balance to know when to leave it out, creativity to avoid clichés and reaching deep within ourselves for authenticity—possibly even exposing some of our hidden inner lives to the entire world.

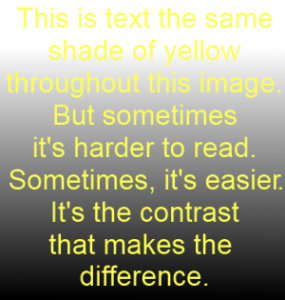

So we can’t just show our character as “in love” or “afraid” all the time—even highly suspenseful or romantic scenes will tend to lose their power when strung together ad nauseam. By incorporating other emotions—even contradictory ones occasionally—we enable our characters to come to life, throw their “main” emotions into relief, and show the many facets of human emotion.

So we can’t just show our character as “in love” or “afraid” all the time—even highly suspenseful or romantic scenes will tend to lose their power when strung together ad nauseam. By incorporating other emotions—even contradictory ones occasionally—we enable our characters to come to life, throw their “main” emotions into relief, and show the many facets of human emotion.