When we’re crafting our characters’ emotions, we want to strive for consistency. Our characters are going to look fickle, insecure or flat-out crazy if it seems like they’re playing “he loves me, he loves me not” in every scene. However, while we want to make sure we preserve the causality chain of emotional responses, if our characters just play the single note of “love” or “fear,” well, that’s the definition of “monotonous.”

So we can’t just show our character as “in love” or “afraid” all the time—even highly suspenseful or romantic scenes will tend to lose their power when strung together ad nauseam. By incorporating other emotions—even contradictory ones occasionally—we enable our characters to come to life, throw their “main” emotions into relief, and show the many facets of human emotion.

So we can’t just show our character as “in love” or “afraid” all the time—even highly suspenseful or romantic scenes will tend to lose their power when strung together ad nauseam. By incorporating other emotions—even contradictory ones occasionally—we enable our characters to come to life, throw their “main” emotions into relief, and show the many facets of human emotion.

Author Brandilyn Collins calls these “main” emotions passions in her book Getting into Character: Seven Secrets a Novelist Can Learn from Actors. She bases her secrets on the methods of acting guru Konstantin Stanislavsky. On passions, she writes (emphasis mine):

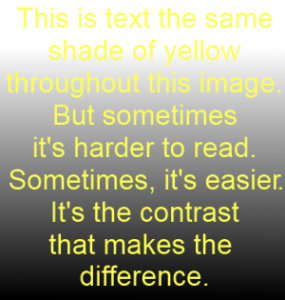

Stanislavsky likens a human passion to a necklace of beads. Standing back from the necklace, you might think it appears to have a yellow cast or a green or red one. But come closer, and you can see all the tiny beads that create that overall appearance. If the necklace appears yellow, many beads will be yellow, but in various shades. And a few may be green or blue or even black. In the same way, human passions are made up of many smaller and varied feelings—sometimes even contradictory feelings—that together form the “cast” or color of a certain passion. So, if you want to portray a passion to its utmost, you must focus not on the passion itself, but on its varied components. (95)

So by using different aspects of these passions, we can better illustrate the real depth of feeling a person would experience. Instead of constantly hitting the same emotional cues in every single scene, we can change up some of the emotions to explore the real depths of the feeling. And every once in a while, we can even take a break from that passion—dropping a low-tension scene every once in a while to make the high-tension scenes stand out.

What do you think? What are the components of the passions you tend to write most?