On Monday, we talked about the draw of uncertainty in romance. There needs to be an element of uncertainty or conflict between the hero and heroine of a romance for readers to be truly vested and interested in the outcome. Predictability is anathema to a story question.

But sometimes, there isn’t conflict between our leads. Sometimes, the romance between them blossoms and grows without too many problems. I think the potential problem here is obvious—even the description sounds boring.

When the course of true love actually does run smooth, we still need conflict. External conflict is good—but if the story is, at its heart, a romance (or possibly a romance hybrid, like romantic suspense), that external conflict really should impact the developing relationship in some way.

Rather than continuing to speak in the abstract, let’s get concrete. A story where Lucy meets Gary, they fall in love and live happily ever after doesn’t sound compelling. Monday, our example was of Lucy meeting Gary and neither of them could tell—and perhaps weren’t sure themselves—whether they would get together, or how the other felt about him/her.

Today, our example is more along the lines of Lucy meets Gary, and Gary is a cop investigating a murder. It’s possible to write a story where the external plot basically has nothing to do with Lucy and Gary’s relationship. I wouldn’t advise that if you’re trying to write a story with the romance as a main plot. Instead, search for ways for the external plot to intersect with the romance plot.

To my mind, there are two basic categories of this intersection: where the external plot pits the hero and heroine against one another, and where the external plot simply gets in the way of their relationship.

To my mind, there are two basic categories of this intersection: where the external plot pits the hero and heroine against one another, and where the external plot simply gets in the way of their relationship.

For an example of the external plot pitting the hero against the heroine, we’ll go back to Lucy and Officer Gary. Lucy and Gary meet, and they hit it off—until Lucy has information about Gary’s homicide case that she just can’t tell him. Kaye Dacus did this subtly—the police officer hero didn’t have to directly confront the heroine he was investigating—in Love Remains. I do it in at least one of my manuscripts—the heroine has information about the criminals the hero is tracking, but she’s trying to protect him from those criminals, so she steers him away from them at every opportunity.

Alternatively, you could have the external plot simply getting in the way of their relationship. Officer Gary’s murder case interrupts Lucy and Gary’s first date. He stands her up when questioning a witness takes too long. He has to prove his commitment to the relationship by finding a balance between his work life and Lucy. (This isn’t a great example, because that’s kind of life when you’re with a cop, and PS catching a murderer is pretty important, but you get the idea.)

Finally, another way to add a level of conflict to what would be a smooth-course romance—possibly as a subset of the second type of external conflict/love story intersection—is to forbid the romance. This one is a bit harder to do in a contemporary, but many historical settings have rigid rules of fraternization and marriage. However, we can borrow a contemporary example from Shakespeare—their families are enemies, or simply do not understand one another’s cultures. Another contemporary example might be having the hero or heroine already dating someone else, especially someone close to the “real” love interest (best friend, brother, roommate, etc.).

I use this technique in a pretty specialized way in one of my manuscripts: the hero is a priest—or at least the heroine believes he is. (And yes, this is the same MS I mentioned three paragraphs ago. Seriously—read the excerpt and it’ll make more sense.)

What do you think? How do you use external conflict (or like to see it used) to add conflict between the hero and heroine in a romance?

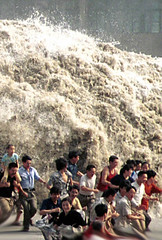

Photo by Paul Morgan

This reversal can stem from some level of autonomy—the character can recognize the problem and make a conscious choice to change—or we can force them to accept the change, give them no other possibilities than to try this new belief system/opportunity/way of life. But either way, to be believable, it’s got to be prompted by external events. As

This reversal can stem from some level of autonomy—the character can recognize the problem and make a conscious choice to change—or we can force them to accept the change, give them no other possibilities than to try this new belief system/opportunity/way of life. But either way, to be believable, it’s got to be prompted by external events. As