Are you ever afraid you’ll run out of ideas? I am. Writing fiction takes up a lot of ideas.

Mostly, I’m not afraid of running out of the high-level, story-starting ideas. Those ideas come from everywhere—watching television, reading the newspaper, reading other novels, brainstorming on other projects, etc. Generally, it takes me two of those big ideas combined to get really excited about a story. And once I’m really excited, I can’t wait to start writing.

But I’m afraid of running out of the little ideas. Things that solve problems on a scene level: tricks to get characters out of (or into!) scrapes, gadgets and technology, historical and cultural facts, and so forth. Sometimes I feel like I’ve been incredibly lucky to come up with the number of ideas (and solutions rooted in my research) that I’ve had in the first place—what if I run out?

But I’m afraid of running out of the little ideas. Things that solve problems on a scene level: tricks to get characters out of (or into!) scrapes, gadgets and technology, historical and cultural facts, and so forth. Sometimes I feel like I’ve been incredibly lucky to come up with the number of ideas (and solutions rooted in my research) that I’ve had in the first place—what if I run out?

Sometimes, I want to save these ideas. “Yeah, I could use this here,” I tell myself. “It might help this scene, but what if I need that exact kind of plot device/gadget/tidbit more in a year or two or five? I mean, I guess I could use it then, too, but won’t that make my writing . . . redundant?”

I’m trying to learn to trust myself—if I have an idea that works for this story that punches it up, I probably shouldn’t wait to see if maybe this story will work okay without it and I can use it later. It’s not “wasting” an idea if you actually put it to use—and who knows if you’ll ever have occasion to use something like that again. And even if you do, chances are that you’ll have to customize it to your characters and their story, so it would probably look very different.

What do you think? Where do you get your “little” ideas and solutions? Do you think something like that might be recognizable? Do you know of any writers who repeat the same plot devices too much?

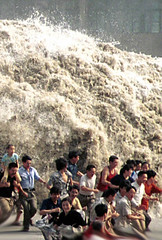

Photo by Steve Koukoulas