So, on Monday, I killed my computer. On Tuesday, I spent 12 hours in airplanes and airports with my two children, ages 3 and 1, by myself.

It’s been a great week. 🙄

Yeah, so back to what I meant to talk about today. A few months ago, I picked up a  storybook to read to my son. It was about 8 pages. It featured trucks, work, and friendships, and . . . well, it sucked.

storybook to read to my son. It was about 8 pages. It featured trucks, work, and friendships, and . . . well, it sucked.

A few days later, I let my husband read it to my daughter for bedtime. Once he finished, I waited for his reaction. He looked up and said, “That book sucked.”

We read a lot of board books, including baby books that are merely lists of items or colors or emotions. We read “I love you” books and song books and silly books all without complaint. So why did this book turn us both off?

It had no plot.

Now, it did have a series of events. Trucks did this, went there, said this. We don’t have a high literary standard for our children’s fare.

But if you’re going to tell a story, your plot has to have conflict. Even if you’re writing for three year olds. Even if you’re writing marketing shlock slapped onto a board book (which this was).

A counter example: we also read The Little Mouse, the Red Ripe Strawberry and the Big Hungry Bear . I’d guess it has somewhere around the same number of words, but the whole book is about the mouse trying to keep his strawberry from the bear.

Conflict. Even in a children’s book. And that one gets requested a lot more than the truck book.

What do you think? Is conflict something we all inherently want in a book?

(If you’re wondering, traveling wasn’t really that bad. They’re pretty good kids. I might even keep them.)

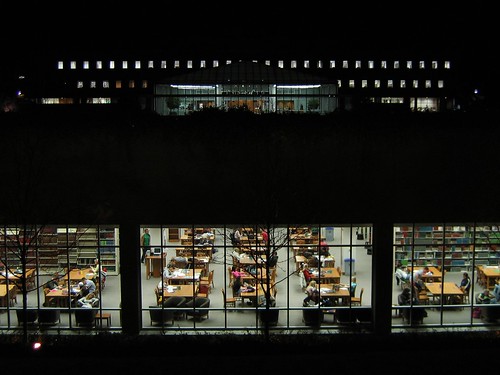

Photo credit: Lawrence Whittemore

From what I understand (as I was told by professors), nearly all MFA programs create a certain type of writer—a literary one. Though I would like to style myself as a literary writer, right now my passions lie in genre fiction, and rare is the program where genre fiction (from romance and mystery to YA to scifi) is not at least stigmatized, if not denigrated. And leaving aside the fact that literary fiction is difficult to write and harder to sell, by no means does an MFA guarantee publication—or even publishable writing.

From what I understand (as I was told by professors), nearly all MFA programs create a certain type of writer—a literary one. Though I would like to style myself as a literary writer, right now my passions lie in genre fiction, and rare is the program where genre fiction (from romance and mystery to YA to scifi) is not at least stigmatized, if not denigrated. And leaving aside the fact that literary fiction is difficult to write and harder to sell, by no means does an MFA guarantee publication—or even publishable writing. have some sort of mental disorder (or live a very different life from me!), this rule leaves no room for fantasy, science fiction, paranormal (well, I suppose that one’s debatable). There would be no Shakespeare or Twain (well, a lot less Twain, anyway) or . . . fiction, when it comes down to it.

have some sort of mental disorder (or live a very different life from me!), this rule leaves no room for fantasy, science fiction, paranormal (well, I suppose that one’s debatable). There would be no Shakespeare or Twain (well, a lot less Twain, anyway) or . . . fiction, when it comes down to it. “Get better at writing” is too vague—if you finally learn the less/fewer rule tomorrow, are you done? We all always want to improve our skills, but a better goal would be to pick a specific skill to work on—to study techniques to create more vivid characters, for example. (It’s still a little vague, of course, but this may be the nature of the beast in this area.)

“Get better at writing” is too vague—if you finally learn the less/fewer rule tomorrow, are you done? We all always want to improve our skills, but a better goal would be to pick a specific skill to work on—to study techniques to create more vivid characters, for example. (It’s still a little vague, of course, but this may be the nature of the beast in this area.) I don’t mean literally broken—I mean that your goals, especially your big goals, should be broken down into specific steps. “Write better” is already kind of broken down if you go with more specific things like creating more vivid characters. But even that can be broken down: read such-and-such a book (by Feb 15), take notes; discuss these techniques with/at X; brainstorm application; spend two weeks going through manuscript to apply notes, etc.

I don’t mean literally broken—I mean that your goals, especially your big goals, should be broken down into specific steps. “Write better” is already kind of broken down if you go with more specific things like creating more vivid characters. But even that can be broken down: read such-and-such a book (by Feb 15), take notes; discuss these techniques with/at X; brainstorm application; spend two weeks going through manuscript to apply notes, etc.![top 9 of 2009_thumb[2] top 9 of 2009_thumb[2]](http://jordanmccollum.com/wp-content/uploads//top-9-of-2009_thumb2.jpg)

For the stuff that’s just off-base, it’s annoying. But for the things that come with that extra note of spite, it’s even harder. This is why I’ve come up with my coping mechanisms—if two other people agree with me, if I can just laugh at it sooner (and laugh at myself), then maybe I can move on faster, right?

For the stuff that’s just off-base, it’s annoying. But for the things that come with that extra note of spite, it’s even harder. This is why I’ve come up with my coping mechanisms—if two other people agree with me, if I can just laugh at it sooner (and laugh at myself), then maybe I can move on faster, right? If you think there might be some merit to some advice (somewhere), or if you’re worried you’re the one with the case of the crazies, turn to someone you trust (especially someone who’s read the story).

If you think there might be some merit to some advice (somewhere), or if you’re worried you’re the one with the case of the crazies, turn to someone you trust (especially someone who’s read the story).