Gearing up for NaNo? That’s okay, I don’t begrudge you, even if I won’t. In fact, I’ll even do what I can to help you prepare. The series on plotting will be in PDF form this week (by some miracle) and today I have a guest post on frequent-commenter-and-guest-poster Carol/Careann’s blog. Check it out: beating writer’s block.

All posts by Jordan

Share your favorite plotting resources

I’m getting ready to make our series on plotting into a free PDF. In one of my free writing guides, I included some “bonus features”—resources that weren’t posted on my blog in the original series, but that are pretty darn awesome.

I’m getting ready to make our series on plotting into a free PDF. In one of my free writing guides, I included some “bonus features”—resources that weren’t posted on my blog in the original series, but that are pretty darn awesome.

I’ve been collecting bonus features again this time around, and I have a few. But I’d love to see your favorite resources and methods for plotting.

What do you use to plot? Share your favorite resources in the comments and I’ll include an attribution link for you in the free PDF version of the plotting series!

Photo credits: question—Svilen Mushkatov

Why I (probably) won’t NaNo

I have intended to participate in the National Novel Writing Month since . . . 2006. (That’s a little odd to me, since I don’t consider myself active writing fiction in 2006, but I did intend to, and even tried, even though I didn’t find out until November was already underway.) NaNoWriMo is a fun method to kill yourself go from nothing to half a novel (50,000 words) in 30 days.

And, like I’ve said above, I’ve intended to participate, but . . . for three years now, I never have, and this year will probably be the fourth.

And, like I’ve said above, I’ve intended to participate, but . . . for three years now, I never have, and this year will probably be the fourth.

The first year, I gave it a shot, but only came up with a couple thousand words. The next year, I’d just finished a 42,000-words-in-under-four-weeks reinitiation to writing fiction, and I was tired.

Last year, I saved a pretty good idea to do for NaNo. I had a chapter-by-chapter chart of post-it notes (which is still hanging in my room)—but by October, my heart just wasn’t in it anymore. Then I had another idea and I just couldn’t wait. I started on October 21 (happy anniversary, book!). Eight weeks and >80,000 words later (I forget that first draft count), I was done.

The thing that gets me about NaNo? I’ve definitely written 50,000 words in 30 days or less, or even a calendar month. But you can’t be a NaNo “winner” unless you have absolutely not one single word in your novel (plotting aside) on 1 Nov and 50,000 words by midnight 30 Nov. The rules say that it’s not 50,000 more words than you had on 1 Nov—it’s 0-50,000 or nothing. And just forget about doing it any other time of year, okay?

Yeah, I understand about camaraderie and all that—but really, if we have to churn out a minimum of ~1700 words/day, 7 days a week, who has time for a lot of online socializing? (It takes me about 3 hours, on  average, to get 1700 words a day, but I have a job and two kids. That’s all the free time I get.)

average, to get 1700 words a day, but I have a job and two kids. That’s all the free time I get.)

So this year, once again, I’m not participating. I just finished another billion word a day draft, and I’m tired. I’m recovering. I came extremely close to burnout with a 1700 words/day minimum for over a month, and I’m just not ready to go back there right now. You enjoy your NaNo; I’m going to go get reacquainted with these people living in my house, and attack the 18″ TBR pile.

What do you think? Will you NaNo? Why?

Photo credits: tapping pencil—Tom St. George; flying fingers by The Hamster Factor

Am I Not a Man? The Dred Scott Story by Mark Shurtleff – Review

You probably can’t tell this from reading this blog, but I used to teach (as a TA, but still, 3-4 classroom hours a week) a college class on American constitutional history (and political science and economics). You want to know how the Constitution came about, and how it’s evolved since then? I’m your lady.

Abolitionists (specifically William Lloyd Garrison) called the original Constitution “A compact with hell.” (He was a fiery type.) The practice of slavery was antithetical to the principles the Union was founded upon.

Mark Shurtleff’s new novel, Am I Not A Man? The Dred Scott Story, tell the story of a landmark case in constitutional support for slavery.

Dred Scott, his wife and two daughters (one of whom was born in free territory) were taken to a free territory by their master. The legal precedent at the time was “once free, always free”—if a master took a slave to a free state/territory, they were considered freed, and if they returned to a slave state, they must be released.

Ultimately, the Supreme Court reversed this decision, relegating the African Americans to the status of property, not human before the law in 1857. Although later freed (because his widowed owner remarried to a prominent abolitionist Congressman), Dred died before the beginning of the bloodiest war in American history, the 13th Amendment (which abolished slavery—not the Emancipation Proclamation, folks!), and the 14th Amendment (which made former slaves full citizens—well, the men, anyway. While the 15th Amendment gave freed slaves the right to vote, women would wait another 60 years for the vote.).

Although this obviously isn’t something we should be proud of, it’s important to remember and to examine the failings in our history. The Constitution did inculcate slavery in the founding laws of our land. However, the Constitution is a flexible, living document, and it was amended to overrule the Dred Scott decision.

The Dred Scott Story tells the story of not only this trial, but of the slave who would take his challenge to the highest court in the land.

It’s an important story, and I think this is the fullest fictionalized treatment that the story had received. Sometimes the story was a little more concerned with telling us history than making history compelling by focusing on the characters. A few times we veered into melodrama, and occasionally Dred came off as a little too much of the “noble savage” archetype.

But it’s not hard to overlook those things (and because I received an ARC, I was probably more harsh than I would be if I had picked up the book on my own). Edited to add: the more I’ve considered this review, I realized that I wanted to add that this book really does make Dred Scott come alive. And in the end, that is how we can make history accessible, and truly learn from it, in a way no other words on a page can—through the eyes of someone who was there. (Though I really wanted there to be a historical note—I always wonder what details were real, and which ones were invented in a historical novel!)

This story is one that we should all know and understand, so that we can recognize our historical collective shortcomings, and never allow that kind of injustice to be perpetuated again.

The End

Well, that wraps up our series on plotting. It’s been fun, hasn’t it? We’ve learned about the three act structure, the snowflake method, the Hero’s Journey and Larry Brooks’s story structure. We’ve seen them applied to fellow writers’ works.

We started off talking about the need for plotting—and of course, there are still going to be some of us that don’t believe in plotting. The arguments are the same (and I used to make them myself)—plotting kills our creative drive. Plotting is boring. Plotting is stifling.

We started off talking about the need for plotting—and of course, there are still going to be some of us that don’t believe in plotting. The arguments are the same (and I used to make them myself)—plotting kills our creative drive. Plotting is boring. Plotting is stifling.

And no, there’s no plotting method out there that will manufacture ideas for us, but there are lots that help us imagine the types of ideas that will move our stories forward. And yes, the joy of writing is in creating and discovering the twists and turns—but knowing what landmarks we’re shooting for can make sure we don’t end up going in circles, or remodeling a Winchester Mystery story, where two thirds of it will have to be jettisoned before we could ever hope to create a livable structure.

Plotting doesn’t have to mean you write out a scene-by-scene outline. When I plotted my most recent MS (using Story Structure), I had the beginning, five landmarks, a twist and the end in mind, plus a freewrite brainstorm of backstory/ideas/plot (about 3 pages). Right now, a lot of the transitions need work, but I never felt lost, never got stuck because I wasn’t sure where I was going and finished the first draft in about 55 days. I know it has a solid backbone, even if some of the stuff in between is a little flabby—and that’s not bad shape to be in after the first draft (not to mention eight weeks, and I took a couple weeks off in there, too).

When we plot, we have to do what works for us. So many of the writers we had guest posts from over the last few weeks mentioned how they customized that plotting method to meet their needs.

If you’ve never plotted before, or if you’ve never successfully plotted before, why not give it a try?

What do you think? What’s keeping you from plotting? Or are there any other plotting methods you like?

Setting up the story question

We discussed the Story Question at the beginning of our series on plotting. The more we’ve discussed plotting, however, the more I realize I have more to say on this topic.

The first time we talked about it, we defined the story question like this (well, we’re using different emphasis this time):

The story question is the basic concept of the story. It’s asked (or hinted at) at the beginning of the story, and answered by the end. It’s the controlling, overarching action of the story.

So how do we hint at the story question at the beginning, especially if we don’t plan to formally ask it until the Call to Adventure, or Plot Point #1?

So how do we hint at the story question at the beginning, especially if we don’t plan to formally ask it until the Call to Adventure, or Plot Point #1?

In all the plotting paradigms we’ve looked at, there’s a period at the beginning of the story where we get to see the character’s world: the Ordinary World, the Setup. Note that the three act, the five act and Brooks’s story structures all place the transition from this world at the 1/4 point, where we’re introduced to the BIG conflict.

But how can we introduce the story question in the beginning if we can’t actually “ask” it for some 25,000 words?

As we show the Ordinary World, we have to show something is wrong there—something is missing. Something is lacking—something that the conclusion of our story will bring to him or her.

If it’s a romance, we need to see in the beginning that the hero and heroine are lacking something—they’re alone. If it’s a mystery, we need to see a lack of justice (which an unsolved murder portrays nicely). Perhaps our main character is naive (or jaded), and the end of the story will bring knowledge or wisdom (or crack his hard exterior).

That doesn’t mean, however, that our characters have to spend the first quarter of the book whining about how lonely they are, and it doesn’t mean we have to wait until the 1/4 point to introduce them (conversely, we aren’t obligated to have them meet, sparks flying, on page 1, line 1).

We have to have conflict in the Ordinary World. If you’ll recall, in The Incredibles, this conflict related directly to the main plot—each member of the family was having a hard time, challenged by the Ordinary World. When we ask the story question (well, at each of the turning points), the stakes are raised for each member of the family.

This conflict in the Ordinary World should relate to the main plot. Imagine if we spend 25,000 words worrying about whether Pa’s crop will come in, and at the 1/4 turning point, we ask if Angelica can find true love. Can you imagine readers’ whiplash—and disappointment (or even outrage) that they just wasted X amount of time reading about something that has nothing to do with the story? That all those characters we cared about don’t matter anymore?

Even if we ask if Angelica can find Pa’s murderer, was the treatise on chopping cotton really necessary? Only if someone killed him for his crop, and even then, the first section might need to be adjusted a little to focus on the story question and not the agricultural practices of white sharecroppers in the 1930s.

What do you think? How have you set up your conflict before asking the story question?

Photo credits: question—Svilen Mushkatov

Overview of Larry Brooks’s Story Structure

This is the most recent plotting method I’ve come across. Simply called “Story Structure,” this method gives great advice for partitioning your story as well as the major events and turning points. I used it in my most recent WIP (which I reached the end of late Saturday night 😀 ), and it was really helpful to pace myself (though I ended up short on word count, I know I’ll add more in revisions).

Larry Brooks, author of many, many scripts, four published novels, and the blog StoryFix, published this in a blog series. It’s very much worth it to read the Story Structure full series, but I’ll give a quick overview here.

Larry Brooks, author of many, many scripts, four published novels, and the blog StoryFix, published this in a blog series. It’s very much worth it to read the Story Structure full series, but I’ll give a quick overview here.

The structure is in four parts with three turning points separating them (plus two “pinch points”). Each part of the story should be about one quarter of the story.

Part one is the Set-up. In this part of the story, we meet the characters and are introduced to the story question. (If you’re reading this and thinking “Oh, the Ordinary World,” you’re not alone.) Here we also establish what’s at stake, but most of all, we’re working up to the turning point at the end of this part: Plot Point 1 (what we commonly call the Inciting Incident).

Brooks says that First Plot Point is the most important moment in your story. Located 20-25% of the way into your story, it’s

the moment when the story’s primary conflict makes its initial center-stage appearance. It may be the first full frontal view of it, or it may be the escalation and shifting of something already present.

This is a huge turning point—where the whole world gets turned on its head. (If you like, you can say this is where we formally pose the story question.)

PP1 bridges into Part 2—the Response. The hero/heroine responds to the first  plot point. This response can be a refusal, shock, denial, etc., etc. That doesn’t mean they have to do nothing—they have to do something, and something more than sitting and stewing—but their reactions are going to be . . . well, reactive. The hero(ine) isn’t ready to go on the offensive to save the day quite yet—they’re still trying to preserve the status quo.

plot point. This response can be a refusal, shock, denial, etc., etc. That doesn’t mean they have to do nothing—they have to do something, and something more than sitting and stewing—but their reactions are going to be . . . well, reactive. The hero(ine) isn’t ready to go on the offensive to save the day quite yet—they’re still trying to preserve the status quo.

In the middle of this part (about 3/8s of the way through your story), comes Pinch Point 1. Brooks defines a pinch point as “an example, or a reminder, of the nature and implications of the antagonistic force, that is not filtered by the hero’s experience. We see it for ourselves in a direct form.” So it’s something bad that we get to see happen, showing us how bad the bad guy is, raising the stakes.

At the end of the Response comes the Mid-Point. As the name suggests, this is halfway through the story. And here, the hero and/or the reader receives some new bit of information. It’s pretty important, though—this is the kind of revelation that changes how we view the story world, changing the context for all the scenes that come after it.

Then we swing into Part Three, the Attack. Now our hero(ine) is ready to go on the  offensive. He’s not going to operate on the bad guy’s terms anymore—he’s taking matters into his own hands, and he’s going after the bad guy. This is the proactive hero’s playing field now.

offensive. He’s not going to operate on the bad guy’s terms anymore—he’s taking matters into his own hands, and he’s going after the bad guy. This is the proactive hero’s playing field now.

In the middle of this part (5/8s of the way through the story), comes Pinch Point 2, which is just like PP1—a show of how bad the bad guy is.

Part Three ends with a lull before the Second Plot Point, our last new information in the story. This last revelation is often the key to solving the mystery or fixing the problem—it’s the last piece of info the hero needs to make his world right. This comes 75% of the way into the story.

And now we’re ready for Part Four, the Resolution. Our hero steps up and takes the lead for the final chases, the last showdowns. Here we get to see how much of a hero he really is—he passes his final tests, proves he’s changed and finally, saves the day.

Simple, right? Uh, kind of. Since examples always help me, we’re going to have a guest post this week talking about how this author is applying this structure to her story. And of course, I need to give credit to the person that pointed out Larry Brooks’s story structure to me, Jaime Theler.

What do you think? Can you see this in place in your writing, or in other works? What advantages do you see to this method?

Photo credits: structure—Christopher Holland; gasp—Becka Spence; attack—D. B. King

Cons of the Hero’s Journey (and a winner!)

No plotting method is perfect—though a lot of Hero’s Journey fans may tell you that the HJ comes close 😉 . However, academics and scholars have pointed out some weaknesses in using the Hero’s Journey as a template for a novel or movie.

On a scholarly level, many point out that Campbell’s theories (the basis for Vogler’s, if you’ll recall) may not really be supported by the full body of mythology and fairy tales. He uses the Western canon, and even then, not the worldwide canon, to support his theories, and within mythological studies today, most consider his work an overgeneralization at best.

As Eileen mentioned in the comments yesterday, the Hero’s Journey can sometimes seem a little formulaic. However, that’s not always a bad thing. Romance, mysteries/thrillers/suspense, and inspirational novels are all “formulaic”—they have a prescribed formula, and if you break with it, well, good luck with the audience. Fans of those genres read them because they know how they’re going to turn out, and that reaffirmation is powerful.

As Eileen mentioned in the comments yesterday, the Hero’s Journey can sometimes seem a little formulaic. However, that’s not always a bad thing. Romance, mysteries/thrillers/suspense, and inspirational novels are all “formulaic”—they have a prescribed formula, and if you break with it, well, good luck with the audience. Fans of those genres read them because they know how they’re going to turn out, and that reaffirmation is powerful.

On the other hand, some do believe that adhering to the Hero’s Journey had produced a lack of originality and clichés in pop culture, especially in movies. (However, I still think it’s versatile enough to use—just try to give your story events a fresh twist. Isn’t that what we should be doing anyway?)

Finally, the Hero’s Journey isn’t all that kind to women—and not just because it’s not called the “Heroine’s Journey.” While it’s certainly possible to use a woman instead of a man as a protagonist, Campbell’s archetypal roles for women include mother, witch and damsel in distress. Not exactly a strong, empowered female role model, eh?

Critical analysis aside, however, the Hero’s Journey can still be a good model for plotting a story—even if it doesn’t magically give you the story events that will make your story a perfect, marketable marvel.

Next week, we’ll take a look at another plotting method that helps you not only plot but also pace your story events.

And before we end here, of course, we have to announce our winner of a free copy of The Everything Guide to Writing a Romance Novel. After taking out comments from me, Faye and her co-author Christie, and using the a random integer generator, the winner is <drum roll please>

Stephanie of Write Bravely

Congratulations, Stephanie. If you’ll send me your mailing address, I’ll pass it along to Faye and she’ll get the book out to you ASAP.

How has the Hero’s Journey fallen short for you and your story telling?

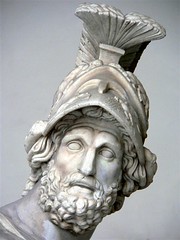

Photo by Mary Harrsch