No plotting method is perfect—though a lot of Hero’s Journey fans may tell you that the HJ comes close 😉 . However, academics and scholars have pointed out some weaknesses in using the Hero’s Journey as a template for a novel or movie.

On a scholarly level, many point out that Campbell’s theories (the basis for Vogler’s, if you’ll recall) may not really be supported by the full body of mythology and fairy tales. He uses the Western canon, and even then, not the worldwide canon, to support his theories, and within mythological studies today, most consider his work an overgeneralization at best.

As Eileen mentioned in the comments yesterday, the Hero’s Journey can sometimes seem a little formulaic. However, that’s not always a bad thing. Romance, mysteries/thrillers/suspense, and inspirational novels are all “formulaic”—they have a prescribed formula, and if you break with it, well, good luck with the audience. Fans of those genres read them because they know how they’re going to turn out, and that reaffirmation is powerful.

As Eileen mentioned in the comments yesterday, the Hero’s Journey can sometimes seem a little formulaic. However, that’s not always a bad thing. Romance, mysteries/thrillers/suspense, and inspirational novels are all “formulaic”—they have a prescribed formula, and if you break with it, well, good luck with the audience. Fans of those genres read them because they know how they’re going to turn out, and that reaffirmation is powerful.

On the other hand, some do believe that adhering to the Hero’s Journey had produced a lack of originality and clichés in pop culture, especially in movies. (However, I still think it’s versatile enough to use—just try to give your story events a fresh twist. Isn’t that what we should be doing anyway?)

Finally, the Hero’s Journey isn’t all that kind to women—and not just because it’s not called the “Heroine’s Journey.” While it’s certainly possible to use a woman instead of a man as a protagonist, Campbell’s archetypal roles for women include mother, witch and damsel in distress. Not exactly a strong, empowered female role model, eh?

Critical analysis aside, however, the Hero’s Journey can still be a good model for plotting a story—even if it doesn’t magically give you the story events that will make your story a perfect, marketable marvel.

Next week, we’ll take a look at another plotting method that helps you not only plot but also pace your story events.

And before we end here, of course, we have to announce our winner of a free copy of The Everything Guide to Writing a Romance Novel. After taking out comments from me, Faye and her co-author Christie, and using the a random integer generator, the winner is <drum roll please>

Stephanie of Write Bravely

Congratulations, Stephanie. If you’ll send me your mailing address, I’ll pass it along to Faye and she’ll get the book out to you ASAP.

How has the Hero’s Journey fallen short for you and your story telling?

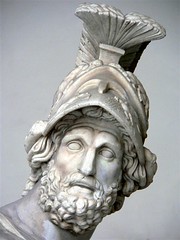

Photo by Mary Harrsch

Thanks Jordan and Faye. I can’t wait to get the book and put it to use.

Congrats, Stephanie!

And, Jordan, thanks again for having me here.

Faye

Jordan,

*delurking again to admit that I lurk* 🙂

For me, the Hero’s Journey helped come up with ideas for that middle section, but it still leaves a daunting amount to fill in for that long Act II. After I came up with the events that would occur in my middle, I kind of had to forgo thinking about the structure and I just had to let things flow naturally from one event to the next. I think this was a good thing in the end because I discovered I needed more scenes to lead from event “a” to event “b” (which helped fill in the Act). But if I strictly adhered to the HJ structure, I would have tried to force “a” to directly lead to “b” and things wouldn’t have flowed as well. Now the events don’t seem like something stuck into the story just to add excitement in the middle, they grow out things that came before so the reader doesn’t question why anything happens.

Thanks!

Jami G.

Congrats again, Stephanie!

Thanks again, Faye!

JG—that’s a great point. Your process reminds me of what I had to do with my last MS. I used the Hero’s Journey (not the writer’s journey, a version with all of Campbell’s steps), and I set goals for how many words I needed to have at certain points to make sure I got enough words. When I was WAAAY behind, I stopped and made myself double the word count so far, which added a bunch of new scenes that revealed the characters and their conflicts better. I might lose some of that in revisions&mdah;but I might not. 😀

Oh, and PS, you’re welcome to lurk, of course, but you’re always welcome to comment, JG 😉 .

Even Vogler says that “The Writers Journey” should NOT be used story template (although it can be). I think there are some absolute must-haves, like Crossing the Threshold (A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step), some kind of Ordeal (no conflict=no story), and some kind of Resurrection (even if the character dies or fails in the end, he still learns a lesson). The rest of the steps are highly recommended, but don’t have to be consecutive steps. Elements can appear at any time. Mentors can be consulted at any time. Tests occur throughout the novel. Enemies spring up at every step.

I don’t buy the “not for woman” argument, at least not for Vogler’s modern interpretation of it. He mentions that it’s been used for movies like “Titanic,” “Thelma & Louise,” “Pretty Woman,” “A League of their Own,” most modern Disney animated movies featuring heroines, etc, etc.

At its core, the Hero’s Journey is just about facing challenges and self-discovery. I think that’s gender-neutral.

Yes, the HJ is about facing challenges and self-discovery. As I said in the post, we do often see the heroine’s journey, now, but the whole basis of the theory is the canon of Western mythology which has always relegated women to a secondary (and often evil) role—the victim, a supporting character or one of the villains. Even if there’s a female protagonist in these stories, it’s seldom her ingenuity or self-discovery that saves the day. It’s her self-sacrifice or her innate goodness—tropes that tend to oppress women, either placing them on a pedestal as above needing any self-exploration and improvement, or making her ultimately unworthy to live in her own eyes. (And don’t even get me started on the insane murderess archetype in Greek mythology.)

Okay,

A) I want to know more about the insane murderess archetype. Seriously. Sounds kewl, and sounds like the basis of Megan Fox’s new vehicle “Jennifer’s Body.” 🙂

B) I don’t understand what you’re saying. What exactly is the “Heroine’s Journey” and how is it different? Where specifically would it differ from Vogler’s interpretation? I understand what you’re saying about the historical archetypes, but what about the modern version of “A Writer’s Journey”? (Which uses “The Wizard of Oz”, a heroine’s journey, as one of it’s primary examples of The Hero’s Journey).

I’m not saying the the HJ is the answer to everything. What I’m saying is to dismiss it because of the fact that most historical literature and mythology was dominated by men and male tropes is a bit short-sighted. All stories are a way to challenge and/or reinforce the current thinking of gender roles. Now that gender roles have changed, different archetypes will emerge. “The Career Woman.” “The Hockey Mom/Governor.” “Mr. Mom.” I think that’s the beauty of the HJ, it’s ability to adapt as culture changes.

I think it’s a valuable tool to analyze your story, but at some level, like some other commenters have mentioned, it’s not a cure-all. You still have to write the story, you still have to figure out how your character gets from Point A to Point B. His whole Act II structure is so vague as to be meaningless at times. I just think it’s a good starting point.

Insane murderess: Medea, of course (kills her husband’s second wife and father-in-law, both of her own children and her uncle). Clytemnestra (kills her husband and his Trojan-war–spoil concubine, without any indication she was actually jealous). Electra (kills her mother [Clytemnestra]). Lady Macbeth. They’re portrayed as intelligent and calculating—strong, smart women lose their morality and commit insane acts (because doing anything other than lying down and taking the insult of your husband leaving you or your mother killing your father can’t possibly be sane, so let’s show just how crazy they are for reacting at all). I think being imperfectly possessed precludes you from the insanity defense.

I’m not saying that a book with a female protagonist can’t use Campbell’s or Vogler’s model. I’m not saying to dismiss it at all. (I did say, “Critical analysis aside, however, the Hero’s Journey can still be a good model for plotting a story,” right after the note about the inherent sexism in Campbell’s model.) I didn’t even say it wasn’t for women. It’s just important to note that the archetypes that Campbell based this all on aren’t what we want to model our characters on.

Plus, we’ve spent all week extolling the virtues of the Hero’s Journey and it’s important to recognize that, like we’ve both said, it’s not perfect nor a panacea.

“Campbell’s archetypal roles for women include mother, witch and damsel in distress. Not exactly a strong, empowered female role model, eh?”

I see your point but, I just don’t think you can get much bigger than ‘mother’ role. Really? How empowering is it to give birth and nurish a baby from your own body? That’s pretty empowering, strong BIG. And ‘Witch’ IS a strong, empowering female role model. Why assume the Witch always has to be some nasty, evil role?

That’s not the point. Campbell’s archetypes are not based on modern (or even correct—I have an entire blog about empowering mothers) understandings of these roles, but on the traditional tropes that have been and continue to be handed down through fairy tales and mythology (where mothers are secondary characters and witches are villains). Reinforcing these by adhering to his archetypes and models undermines finding empowerment as a woman.