Ah yes, the first writing platitude we all learned: write what you know. According to an article I came across from the New Yorker, that was the prevailing mantra in writing instruction in the 1940s and ’50s (and for the next two decades, it was the also-well-intentioned-but-equally-misguided “show, don’t tell“).

One of the primary evidences people usually give against this rule is the fact that only writing what you know—or, as it seems to say, what you’ve experienced—reduces all writing to autobiography. Unless you  have some sort of mental disorder (or live a very different life from me!), this rule leaves no room for fantasy, science fiction, paranormal (well, I suppose that one’s debatable). There would be no Shakespeare or Twain (well, a lot less Twain, anyway) or . . . fiction, when it comes down to it.

have some sort of mental disorder (or live a very different life from me!), this rule leaves no room for fantasy, science fiction, paranormal (well, I suppose that one’s debatable). There would be no Shakespeare or Twain (well, a lot less Twain, anyway) or . . . fiction, when it comes down to it.

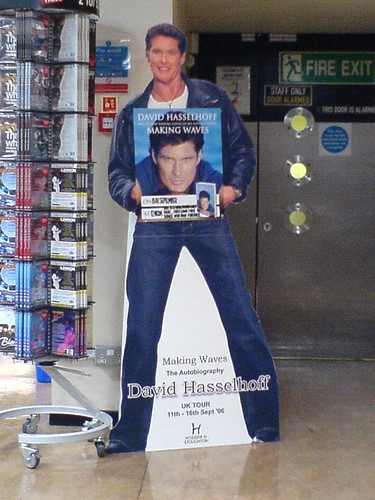

And that’s true. If we were completely limited to only writing about our experiences, the literary world would be a bleak and boring place, rife with . . . well, check out exhibit A at right. Most of us lead very boring lives (and would have no hope of ever receiving a publishing contract). We might be able to fashion some part of our life story into a working narrative, but at most we’d only be able to squeeze out a couple short novels from the whole of our mortal existence.

But that doesn’t mean we should just completely dismiss the “write what you know” rule. It comes, like so many stupid writing rules, from sound principles: know your subject and check your facts. But I think it goes deeper than that, too, and can apply in a way that’s still as relevant to us as it was to Shakespeare, Twain, et al.—and in fact, it’s a reason why their writing is still so powerful and resonant today.

You have to write what you know—and you have to know people. To create compelling characters and thus compelling stories, as writers, we have to intimately know and understand human behavior and emotions. A story where the protagonist does something that seems stupid, self-contradictory or flat-out foreign all the time is frustrating to a reader.

So we need to know—and continue to study and get to know—people. We have to strive to understand human behavior and motivations, how we can get our characters to act in ways we need them to (or how they’d really act and change our story accordingly

And while our lives are likely too narrow and boring to make a good story most of the time, we all understand many of the universal feelings that motivate people—from greed to love to jealousy to anger to joy to grief to heartbreak, we’ve been there in some form. Understanding and remembering our own experiences with these emotions—things that we know—is at the root of creating powerful experiences for the reader.

So do write what you know—but don’t be afraid to make up the rest!

What do you think? In what other ways do you think it’s important to “write what you know”?

Photo by bobcat rock