Or, How writing is like spicy mac

A couple weeks ago, my family went out to lunch. We got a side of macaroni and cheese that was advertised, correctly, as having a little kick to it. The spice was too much for the kids, so my husband and I ended up eating almost all of the macaroni and cheese.

The first few bites were really tasty (and I’m really picky about mac’n’cheese). Within a few bites, the spice began to set in. It wasn’t too spicy—no tears, no runny noses—but I could see why my kids needed water.

The first few bites were really tasty (and I’m really picky about mac’n’cheese). Within a few bites, the spice began to set in. It wasn’t too spicy—no tears, no runny noses—but I could see why my kids needed water.

But once we were halfway through our meal, my husband and I both realized that we weren’t really tasting the mac or the cheese. After a while, all you could taste was the spice.

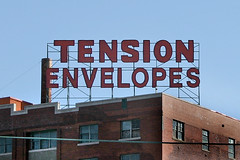

Early on in our writing, we usually learn early on that we need tension and conflict in our scenes. Tension, suspense and conflict are vital, and few people will read fiction without that “spice.”

However, sometimes it’s easy to go overboard on this vital element. At the climax, we’ll probably have a long passage of high-tension scenes, but if every scene of the book features world! threatening! consequences!, all you can taste is the spice—and the book feels just as one-note as if every scene had no tension at all.

Spice isn’t the spice of life—it’s variety. So change up the tension levels in your scenes.

Ten ways to change up the tension in your scenes

1. Use humor. A joke can reduce the tension in a scene, or just give the readers a break from unremitting THE WHOLE PLANET WILL DIE!!! drama.

1. Use humor. A joke can reduce the tension in a scene, or just give the readers a break from unremitting THE WHOLE PLANET WILL DIE!!! drama.

2. Switch storylines. Changing to another group of characters doing something else often helps to vary the tension level. This also works in reverse—if the tension gets too low in one storyline, switch to another, then change back to a point where something more interesting is happening.

3. Bump up your character’s proactivity. Maybe your characters aren’t facing chase scene after chase scene, but they’ve been kidnapped and they’re being dragged around the country, and they’re freaking out the whole time. That level of tension, that helpless response, makes the tension (and the characters!) seem one-note. Don’t let your characters just wring their hands and whine. Do something!

4. Change your character’s goal. If we’ve had five scenes in a row of your characters trying to do the exact same thing, and encountering the same problem, or the same level of problems, something’s got to change. (You know what they say about the definition of insanity?)

5. Change the source of the threat. Maybe your last eight scenes have been at a 7 on the tension scale. You might be able to bump some of them up

6. Use dramatic irony. Dramatic irony is when the audience knows something the characters don’t, usually something that will pull the rug from under the characters. If you have scenes from the antagonist’s POV, for example, you can set up dramatic irony (and switch to that storyline to intercut the tension).

7. Have your characters reach a goal. Throughout the book, we mostly try to frustrate our characters’ goals because it increases the suspense and tension. To change things up, have them accomplish something—it could be something small, like retrieving an important artifact, or it could be something major, like defeating the bad guy (who turns out to be only a minor villain).

8. Give us a campfire scene. Let the characters celebrate and relax, if only for a minute. Especially good after a victory that turns out to be false.

9. Use a sequel. You may not have the time or place to have a celebration scene right now, but if your character has a minute, he or she might be able to go through the stages of an emotional reaction to the action, naturally a bit lower in tension.

10. Show the recovery. You’ve got hearts racing, stomachs clenching and palms sweating (dude, gesture clichés). But do your characters ever stop doing those things? Do they strive to (or just naturally) get their visceral responses under control? Take a deep breath, take a look around, take a minute to reorient your goals before you plunge in again.

Again, tension is absolutely vital to a novel—but having all your scenes with equally high tension is just as stultifying as all scenes with low tension. We don’t want every bite of our meal to taste like plain noodle or like plain spice. Vary the tension of your stories to create a truly engaging taste reading experience.

How else can you vary the tension in your scenes?

Photo credits

Macaroni and cheese by David Berkowitz

Flatline by Myles Grant

both via Flickr/CC

Info dumps, or long, unnatural passages of exposition, are a good way to bore and lose your reader. Sometimes we try to sneak in that

Info dumps, or long, unnatural passages of exposition, are a good way to bore and lose your reader. Sometimes we try to sneak in that