AKA Strategy Before Tactics

Believe me, most authors feel the same way the first time they have to market a book. Maybe you have a few ideas about contests you could do or blogs you could visit, but on the whole, your marketing “plan” feels like a disorganized mess. Good news: using strategies helps you to organize your efforts and focus on the tactics that work for you.

Huh? (The difference between strategy and tactics)

We mentioned this in passing the first week of this series, but as a reminder:

We mentioned this in passing the first week of this series, but as a reminder:

The first things we think of when we think of marketing—search engine optimization, affiliate marketing, email, blog tours, giveaways—are also tactics.

Tactics are the individual things we can do to promote our book, all those online tactics listed above as well as offline tactics like in-store marketing, radio/TV/billboards, etc. Strategies are composed of our goals and plans for using those tactics.

So many people make the mistake of jumping into tactics without considering strategy—but not us!

So, This Strategy Stuff . . . ?

I’ll admit: I focused mostly on the tactics myself when I thought about my (far-off) marketing, up until last year at the LDStorymakers Conference when I attended a fantastic class by Robison Wells on marketing strategy. (Strategery? No.) Rob was so kind as to put his writers’ marketing strategy presentation online (motion sickness warning. I’m not kidding).

Hold on just a minute. I know, I know, we’re talking about marketing and we’re into it, but let me just tell you who this Robison Wells guy is first. 1.) Pertinent to this conversation: he’s an MBA. 2.) Also quite pertinent: he’s a writer. He made his national debut last fall with a YA dystopian novel, Variant (aff). This book. Is. Excellent. And you don’t have to take my word for it—Publishers’ Weekly named it one of the Best Books of 2011.

And back to marketing.

“Without strategy,” Rob says, “those tactics are just a shot in the dark.” Our strategy helps us to determine which tactics to use to suit our books, our audiences, our personalities, and our lives. A strategy also helps us to make sure the messages we send to our consumers, from our books to our blogs to our websites to our tweets, is the one we want to send.

Who Are You

(Why, yes, I do like The Who.)

To figure out this strategy, we first need to understand ourselves, our books, and where we fit in the market. We do need to understand where we fit in a genre and what that audience expects, of course, but we also need to know how our book stands out from and adds to other works in the genre.

Rob offers an example positioning statement to help us find our book’s Unique Selling Proposition, the thing that sets our book apart from others in the market—AKA the reason people will want to read it:

For the reader who wants _______, my book is (genre) that offers _______. Unlike other books in my genre, my book provides ______________.

Be specific and push yourself hard when filling in those blanks! Don’t just go for the first generic thing that pops into your head, and don’t use backhanded compliments or digs at the present state of the market as a way to set yourself apart because you’re “better” than them.

Also, don’t worry about how long this ends up: you’re not giving it as an elevator pitch. You’re using this to help remind yourself the things that are important when you’re creating your strategy and using those tactics to communicate with your audience.

Who’s Your Audience?

To state the obvious, your audience is the people who might be interested in your book. We’re going to ignore the people who are ignoring you, okay? It’s just a recipe for pain otherwise.

We’ve said before that the goal of marketing is to get your product in front of people who would be interested in buying it, i.e. your audience. These are people who read in your genre, read about the types of characters you’re writing, read your style of writing.

It’s vital to understand your own Unique Selling Proposition because it helps you narrow down your audience. I’m sorry, but your audience isn’t “everyone who is young at heart,” or “people aged 6 to 1,836.” In fact, your audience probably isn’t all mystery or romance or sci-fi readers. If you’re writing a cozy mystery, people who read exclusively hardboiled detective novels aren’t your audience.

So let’s say you are writing a cozy mystery. You know you need to target people who read cozy mysteries, right? Now you need to tell them why they should read your book instead of all the other cozy mysteries out there. How is it different from other cozies they’ve read, and how does that appeal to them? What shiny, new, novel novel concept (hehe) are you bringing to the table?

Yeah, this is where all that “market research” comes in. (Oh, come on, you’re reading this stuff for fun, right? If not, maybe you’re in the wrong genre.) You know how your detective is different from Jessica Fletcher, Miss Marple and Jim Qwilleran. You know which quirks and settings and storylines are “taken.” You know how your writing style stands out. Most of all, you know what types of things cozy readers like, and you’re giving them something new that is exactly what they want to see. These are the things that belong in a USP—and your strategy.

Yeah, this is where all that “market research” comes in. (Oh, come on, you’re reading this stuff for fun, right? If not, maybe you’re in the wrong genre.) You know how your detective is different from Jessica Fletcher, Miss Marple and Jim Qwilleran. You know which quirks and settings and storylines are “taken.” You know how your writing style stands out. Most of all, you know what types of things cozy readers like, and you’re giving them something new that is exactly what they want to see. These are the things that belong in a USP—and your strategy.

So, Where Do I Fit In?

Yes, about you. You play a huge role in your strategy, aside from knowing your book and what’s unique about it better than anyone else. Your role in your own strategy is the key player, the mover and shaker—and yes, the marketer.

What does that mean for your strategy? It means that you’re going to have to stick to things you know how to do or are willing to learn. It means that you need to focus on tactics and campaigns you enjoy, do well, can reach your audience through, and, yes, have the time for.

What does that mean for your strategy? It means that you’re going to have to stick to things you know how to do or are willing to learn. It means that you need to focus on tactics and campaigns you enjoy, do well, can reach your audience through, and, yes, have the time for.

I really wish I could tell you how to figure that out, but I do know that you can look at your past Internet habits as a clue to what kind of Internet marketing tactics might work well for you. If you think Facebook is the root of all evil, perhaps set up a page there (so someone else doesn’t!) and don’t do much more. If the thought of blogging gives you thrills & chills—or night sweats—you know what to do.

A lot of people out there will tell you that you should should should do X, Y, and Q7. But worrying about what someone who doesn’t know you or your audience thinks you “should” do—and forcing yourself to use tactics that crush your soul—is seldom a recipe for long term success.

What do you think? What else belongs in a marketing strategy? How do you figure out what tactics are right for you?

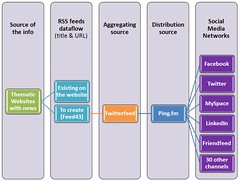

Photo credits: War Games screencap via Dan Brickley; strategy graphic by Sean MacEntee; bookshelf by Josh; social media strategy by Matthieu Dejardins

So what, you ask? Well, those statistics mean that the average girl named Madison is less than five years old right now. When I read these, I couldn’t help but thinking of the curly-haired toddler down the street. Although a strong, androgynous girls’ name is awesome and Madison hits all the right notes with parents and authors alike today, that’s exactly what makes it all wrong when naming a character who’s supposed to be an adult today.

So what, you ask? Well, those statistics mean that the average girl named Madison is less than five years old right now. When I read these, I couldn’t help but thinking of the curly-haired toddler down the street. Although a strong, androgynous girls’ name is awesome and Madison hits all the right notes with parents and authors alike today, that’s exactly what makes it all wrong when naming a character who’s supposed to be an adult today.

)

)

)

)